By 1911, the Qing dynasty had lost its grip on China. Foreign invasions, corruption, and failed reforms had built up decades of anger. The empire was reaching a breaking point.

The Background

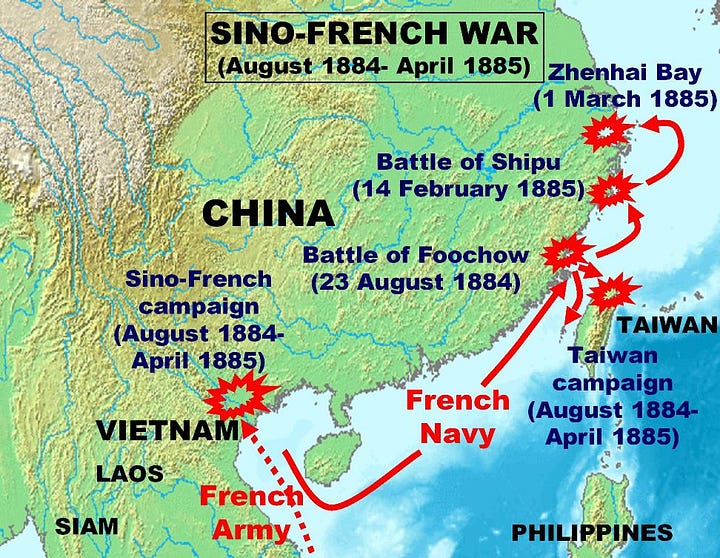

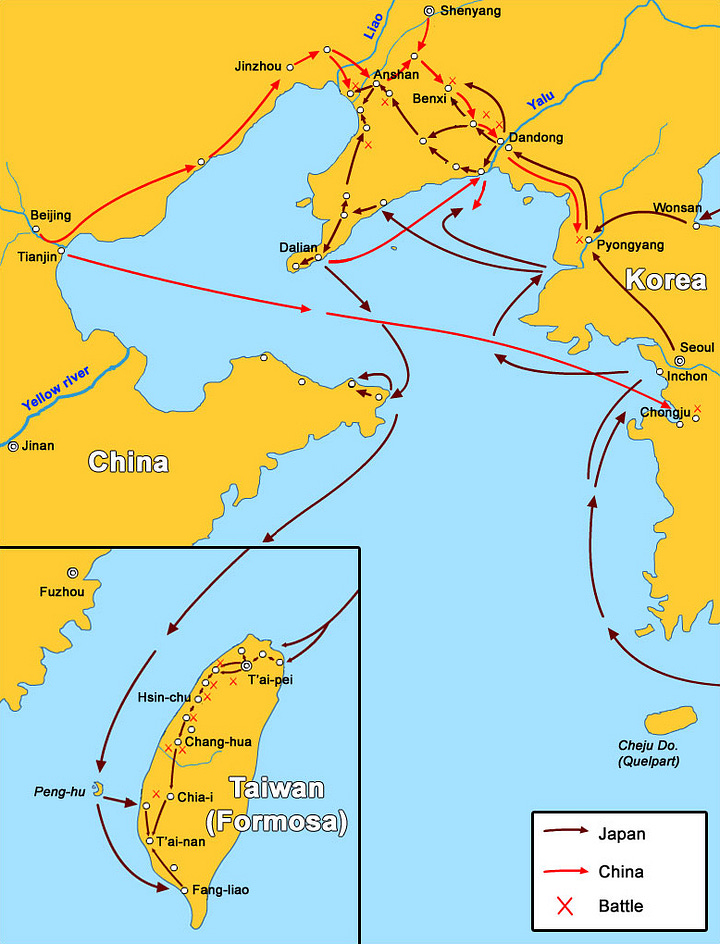

China’s defeats in the Opium Wars, the Sino-French War, and the Sino-Japanese War exposed the Qing as weak and incapable.

Reformers tried to modernize with constitutional monarchy in 1898, but the emperor’s court rejected it.

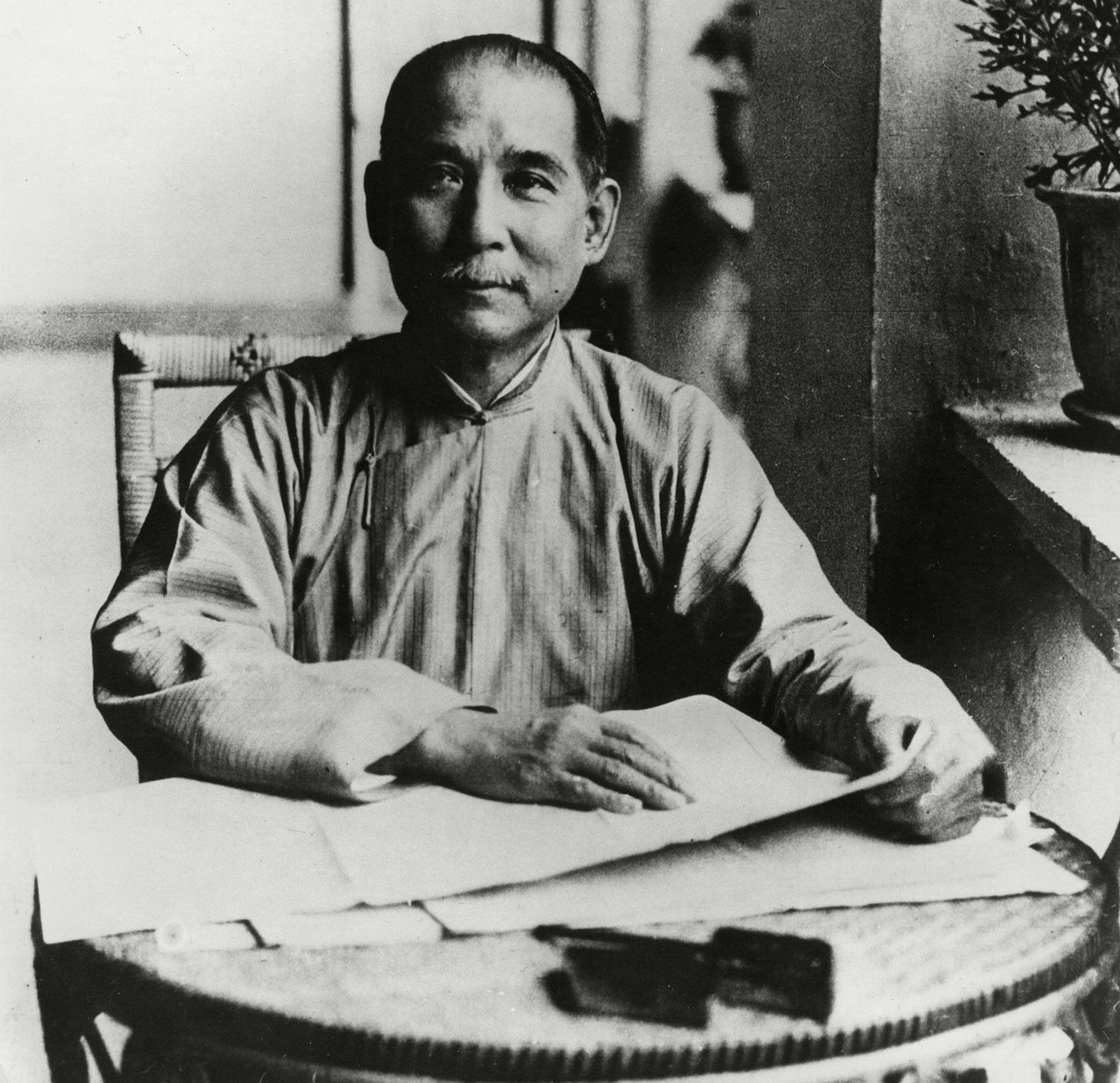

Revolutionaries like Sun Yat-sen called for something new: a republic, based on nationalism, democracy, and livelihood.

The Organizations

Underground groups inside China worked in secret, often at the risk of execution.

Overseas Chinese communities sent money and support.

The Qing’s “New Army,” trained in modern warfare, became a key base for spreading revolutionary ideas. Young officers were often sympathetic to the cause.

The Spark

In 1911, the Qing government seized control of local railways. Many saw this as handing resources to foreign banks.

Massive protests broke out in Sichuan. Government troops opened fire, killing demonstrators.

In Wuchang, revolutionaries hiding weapons and bombs were exposed by accident when an explosion revealed their plans. Facing arrest, they had no choice but to rise.

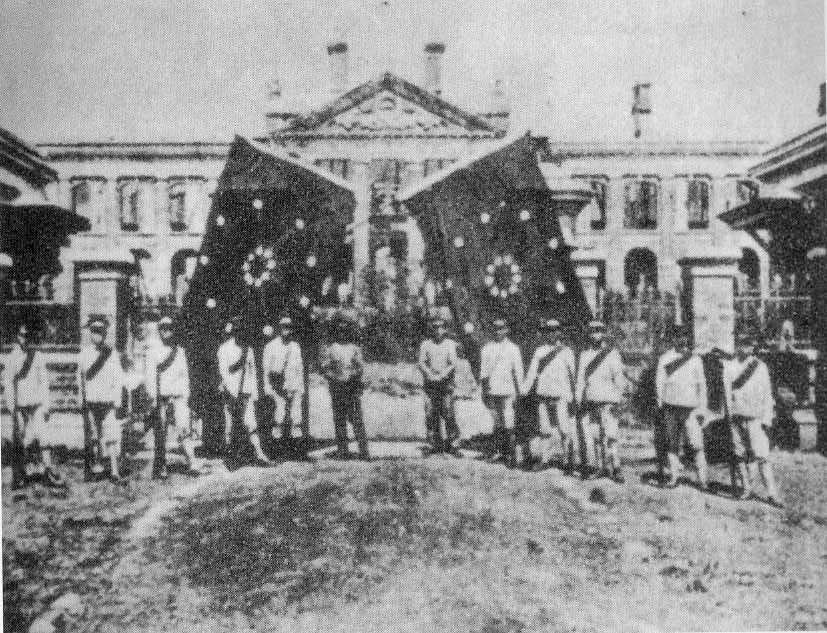

On October 10, the New Army mutinied, seized Wuchang, and set off the uprising. Within weeks, most provinces declared independence.

The Result

On January 1, 1912, Sun Yat-sen became provisional president of the Republic of China.

The Qing dynasty collapsed, ending more than 2,000 years of imperial rule.

Why It Matters

The 1911 Revolution did not appear overnight. It was the product of decades of humiliation, failed reforms, and rising social tension. When pressure reached a critical point, one accident in Wuchang turned years of discontent into a nationwide uprising.

This shows a pattern. Revolutions usually follow the same steps:

Deep social contradictions build over years.

Reform attempts fail or are blocked.

A single trigger breaks the fear barrier.

Revolt spreads as people realize the system can fall.

That is why reform often becomes an illusion. In many democracies today, elections are presented as reform, but they rarely change the system itself. Every four or five years, the party in power may switch, yet the underlying structure remains the same. Elections can create false hope, delaying real change. The lesson of 1911 is that when reform cannot solve contradictions, the pressure eventually explodes into revolution.