Introduction – From High-Speed Rail to High-Stakes Memory

On July 26, 2025, a delegation of Flying Tigers descendants, American students, and the chairman of the Sino-American Aviation Heritage Foundation, Jeff Greene, arrived in Hubei Province, China. It was not just a diplomatic visit or a commemorative tour-it was a living reminder of a bond forged in war and tempered by time.

As their train rolled into Wuhan, Greene looked out at the brilliant skyline and remarked, “I’ve seen China’s incredible transformation-but what we must never forget is the moment when Americans and Chinese stood shoulder to shoulder in the skies above.”

This visit isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about choosing memory over erasure. In an era where U.S.-China relations are defined by suspicion and rivalry, the story of the Flying Tigers offers something rare: shared sacrifice.

Part I: Who Were the Flying Tigers?

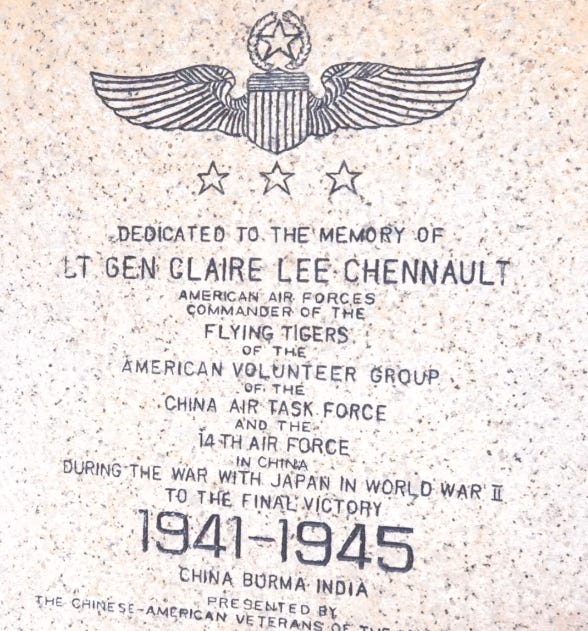

Officially known as the American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Chinese Air Force, the Flying Tigers were formed in 1941 under the leadership of retired U.S. Army Air Corps officer Claire Lee Chennault. Before the U.S. formally entered World War II, these American pilots flew under Chinese command to fight the Japanese invasion.

Why “Flying Tigers”? Their aircraft were painted with menacing shark teeth on the nose-a design that became iconic. But it was their results, not their artwork, that made them legends.

Part II: What Did They Achieve in China?

1. Formation and Early Strategy

The Flying Tigers were authorized secretly by the U.S. government but operated under Chinese command and funding. Recruited from the U.S. military, they resigned their commissions to serve in China.

2. Combat Achievements

Though only active for about 7 months (December 1941–July 1942) as an official unit, their combat performance was staggering:

296 Japanese aircraft destroyed with only 14 American planes lost.

Disrupted Japan’s logistics lines in Burma and China.

Protected the Burma Road-China’s vital supply lifeline.

After disbanding, many AVG members transitioned into the 14th U.S. Air Force, which continued operations over China until Japan’s surrender in 1945. By war’s end, the Flying Tigers and their successors had downed over 2,600 enemy aircraft.

3. A People-to-People Alliance

Over 200 Flying Tigers pilots were rescued by Chinese civilians after being shot down. Thousands of Chinese gave their lives to shelter and protect these foreign allies.

One of the most moving examples is “Flying Tigers Village” in Hubei. In 1944, a U.S. fighter pilot named Bennida was shot down and rescued by villagers at great risk. That act of courage led to the eventual renaming of three local villages in 2017 as “Flying Tigers Village” to honor this moment of transnational solidarity.

Part III: Chennault – The Man Behind the Mission

General Claire Chennault was more than a pilot. He was a visionary. He saw air power as essential to resisting Japanese aggression and lobbied relentlessly in Washington to aid China before Pearl Harbor.

He personally advised Chiang Kai-shek and coordinated U.S.-China military strategy.

After WWII, he married Anna Chan Chennault, a Chinese journalist and political figure.

Until his death in 1958, Chennault remained an advocate for Sino-American friendship, even as Cold War politics strained ties.

Part IV: Remembered in China, Forgotten in the West

In China, the Flying Tigers are enshrined in textbooks, museums, village names, and oral history. Their legacy is publicly honored as part of the anti-fascist struggle.

In the U.S., however, they are mostly forgotten-overshadowed by the Pacific theater, Normandy, or the Manhattan Project. Even though the China front bled 30 million lives, it barely registers in Western popular memory.

Jeff Greene, who has spent 30 years working to preserve the Flying Tigers’ legacy, put it bluntly:

“Most Americans don’t know this history. But China remembers. And because they remember, the story continues.”

Part V: Flying Tigers 2.0 – Passing the Torch

In 2022, Greene’s foundation launched the Flying Tigers Friendship School & Youth Leadership Program, now linking nearly 100 Chinese schools and over 40 American schools. Through exchanges, video calls, and student visits, a new generation is learning that U.S.-China relations weren’t always defined by tariffs and TikTok bans.

This week in Hubei, Greene and his team are visiting multiple schools to expand the program. His goal?

“Next year, we’ll bring Chinese students to the U.S. to continue the work. Education and cooperation-not isolation-will define real leadership.”

Conclusion: Choosing Memory Over Rivalry

The Flying Tigers didn’t come to China for conquest, exploitation, or dominance. They came to help. And they bled for it. Over 2,000 died on Chinese soil. That matters.

At a time when the word “enemy” is again echoing across the Pacific, it’s worth remembering:

Once upon a time, Americans and Chinese flew together against fascism.

Once upon a time, they buried their dead together in the same soil.

Once upon a time, we were not adversaries-but allies.

That story is not just history. It’s a mirror. The question is-do we dare look into it?