When Enforcement Keeps Failing, Look at Training, Not Just Intent

ICE isn’t just “messy,” it’s often meant to be scary

ICE has dominated headlines for days. Public raids, aggressive tactics, cities describing fear and disruption, and encounters that escalate instead of calm. Some people frame this as bad judgment or poor professionalism. That explanation is incomplete. Some of what we are seeing is absolutely intentional.

This is not just about ICE. It applies to policing in the United States more broadly, and it has for a long time. When enforcement repeatedly escalates situations instead of de-escalating them, the standard response is predictable: the officers were not trained well enough. That is partly true, but it avoids a deeper and more uncomfortable question.

The real question: not only “how much training,” but “what is policing for?”

The real issue is not only how much training law enforcement receives. It is what they are trained to do, and even more importantly, what policing is defined to be.

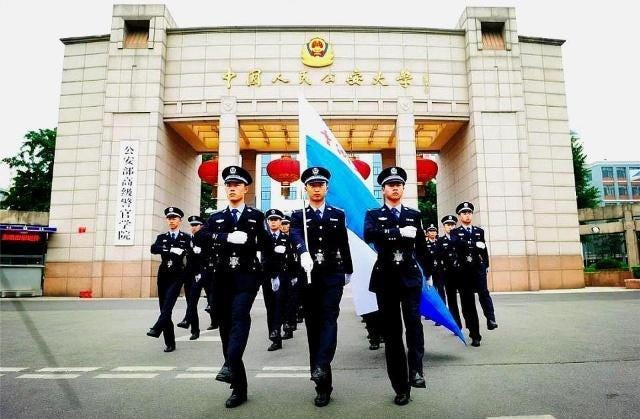

In China, the term is “People’s Police,” the implied purpose is service and social stability through restraint.

In the United States, law enforcement often functions as an arm of state violence, the implied purpose becomes control and compliance.

Those two definitions shape everything downstream, including what behaviors get rewarded, what mistakes get tolerated, and what outcomes become normal.

China’s model: policing as a professional career track

China treats policing as a long-term professional track, not a rapid hiring pipeline. Future officers typically attend police colleges or public security universities for around three to four years. Authority comes after formation, not before.

What they study

Training is structured to build legal discipline and procedural restraint, not just tactical capability.

Law and legal procedure

Evidence rules and case handling basics

Public order management and crowd control concepts

Crisis response and escalation control

Discipline, command structure, and professional norms

Limits on the use of force

Who gets in

Entry is filtered, not open-ended.

Screening and background checks

Physical standards and fitness testing

Additional vetting that aims to exclude unsuitable candidates before they gain authority

The core assumption is simple: authority without restraint is dangerous, and legitimacy depends on discipline and professionalism.

The U.S. model: speed, fragmentation, and learning under pressure

The U.S. model operates differently. Training is fragmented across thousands of departments, and there is no real national standard. In many jurisdictions, police academy training lasts weeks or a few months. Officers are hired quickly, trained quickly, then pushed onto the street with weapons, broad discretion, and legal protection. Learning happens in real time, under pressure, with irreversible consequences.

That structure tends to produce predictable patterns:

Inconsistent standards across agencies and cities

Escalation as the default under stress

Procedural errors that would be less likely under deeper formation

“Force capacity” prioritized over professional judgment

This is not an accident. It is a design choice.

The budget excuse: the U.S. has money, it just spends it elsewhere

When critics suggest longer training, the immediate response is budgetary: the U.S. cannot afford multi-year professional formation. That argument collapses under scrutiny. The United States already spends enormous sums on enforcement. The issue is not money, it is priorities.

Money routinely flows to:

Tactical gear and militarized equipment

Overtime-heavy deployment models

Surveillance tools and operational expansion

Raids and aggressive enforcement activity

Settlements and legal costs after misconduct

If the priority were public service, deep training would be treated as an investment that pays off through fewer escalations, fewer wrongful arrests, fewer shootings, fewer lawsuits, and higher legitimacy. When that investment is not made, it signals purpose, not scarcity.

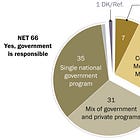

What the incentives reveal: serve the people, or enforce authority?

Training police for years tends to produce officers who hesitate, de-escalate, and question orders. That is good if the goal is public service. It is inconvenient if the goal is control.

Two systems reveal two priorities:

One invests in professionalism to build police who serve the public.

One invests in speed, force, and compliance to build an enforcement apparatus that maintains authority.

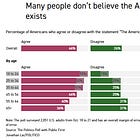

When ICE and police increasingly resemble an occupying force rather than public servants, that is not necessarily the system failing. In many cases, it is the system functioning as designed.

Closing: what the refusal to invest is really saying

If policing were meant to serve the people, deep training and strict formation would be treated as a basic investment, not a luxury. The refusal to make that investment tells us what the system is actually for.

The uncomfortable question is not whether an individual officer acted badly. It is whether the system is built to produce restraint and service, or to produce escalation and compliance.

More stories you might missed…

Policing in America has always been on how it was designed and developed, to control specifically Black people. Ever since, it has become more oppressive and intrusive toward that purpose and intent. This is only what has built American policing to what we see today and everybody partakes in that iniquitous.

There's a bigger subject here, the roots of America's policing is tied historically to slave controls and this guides its impetus even today. There's books written on your subject, excellent post, thank you Grumpy.

Went to China to find the truth…friendly happy very hard working people. Police armed with a notebook and a traffic flag , neighborhood representatives everywhere , they receive your complaints and promptly act on them. What’s the matter with these people…so normal, a civilization to be admired.