China’s Garbage Revolution: From Landfills to Power Plants, From Ash to Sidewalk Bricks

How China turned urban garbage into electricity, construction materials, and cleaner cities.

1. From Landfills to Energy

Twenty years ago, most Chinese cities depended on landfills. They leaked chemicals into groundwater, took up farmland, and caused methane explosions. As urbanization accelerated, cities ran out of space and patience.

Today, that model is being replaced by waste-to-energy plants. These facilities burn garbage at high temperatures to generate electricity. According to China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, over 70 percent of the country’s municipal waste is now incinerated.

Each ton of waste burned can produce 300 to 400 kilowatt-hours of electricity. Nationwide, waste-to-energy plants generate more than 100 billion kilowatt-hours of power every year. That is roughly equal to the electricity use of a mid-sized province.

In wealthy coastal regions like Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, nearly all urban garbage is now processed through incineration.

2. What Happens After Burning

Incineration reduces garbage volume by about 90 percent, but it leaves two main residues: bottom ash and fly ash. Bottom ash accounts for roughly four-fifths of the residue and can be reused after treatment. Fly ash, which contains heavy metals and salts, must be neutralized and stored.

Bottom ash is not waste. After being screened and stabilized, it becomes raw material for construction. Cities such as Changsha and Suzhou use treated ash to make eco-bricks for sidewalks, roads, and public parks.

In official planning documents, this residue is classified as “chemically stable and suitable for brickmaking or road base materials.” The process closes the loop between waste management and urban infrastructure.

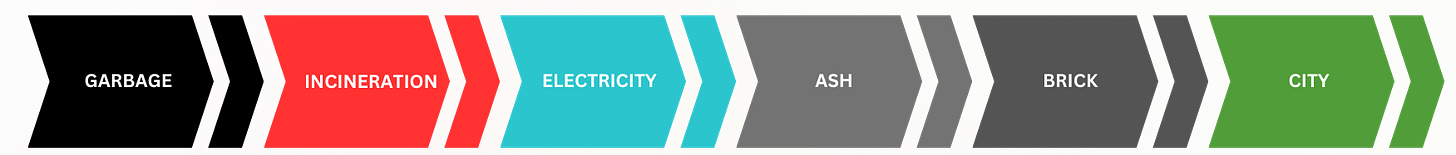

3. How the System Works

The waste-to-energy cycle operates in four main steps:

Garbage is collected and sorted.

The waste is burned to produce heat and electricity.

Bottom ash is treated and recycled into construction material.

Former landfills are cleared, restored, and redeveloped into parks or residential zones.

Some Chinese cities that were once surrounded by garbage now have green belts where landfills used to be. This is not only a technical achievement but also a visible environmental recovery.

4. The Shortage of Trash

As the system has expanded, an unexpected problem has emerged. Garbage is becoming scarce.

Improved waste sorting and recycling mean less combustible material for incinerators. Yet new plants continue to be built. In several provinces, plants are operating below capacity because there is not enough waste to burn.

Some cities now transport garbage from surrounding areas to keep the furnaces running. Others are excavating old landfills to extract buried waste. What used to be an environmental disaster has become an energy resource.

5. The Broader Impact

This shift represents a new stage in China’s circular economy.

Energy: Waste is converted into electricity and heat, reducing reliance on coal.

Land: Old landfills are removed, freeing land for new development.

Resources: Reusing bottom ash reduces the need for mined sand and gravel.

Climate: Burning waste cuts methane emissions from decomposing landfills and helps meet carbon reduction goals.

Waste-to-energy plants are now integrated into the national grid and local heating systems, especially in northern cities where waste heat provides winter heating.

6. Regulation and Standards

Modern plants use two-stage combustion and advanced filtration systems to limit emissions of dioxins, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter.

Provinces such as Hunan, Zhejiang, and Guangdong have issued detailed regulations for ash reuse. Treated bottom ash must pass leaching and toxicity tests before being used in bricks or road materials. Each batch must be recorded in a traceable system to prevent environmental risks.

7. A National Network

China has built more than 400 waste-to-energy plants nationwide. The sector’s market value now exceeds 200 billion yuan.

Different regions focus on different applications:

Shanghai promotes full closed-loop recycling with complete ash reuse.

Shenzhen operates almost entirely without landfills.

Changsha and Ningbo specialize in brickmaking from treated ash.

Northern cities combine waste incineration with district heating systems.

The result is a coordinated network where energy, materials, and environmental management reinforce each other.

8. Conclusion

China has turned one of its biggest urban problems into a national asset. Garbage that once filled landfills now powers homes, supplies heat, and forms the bricks beneath city sidewalks.

In many Chinese cities, old dump sites have become parks, power plants, or housing developments. The same land that once symbolized decay now represents renewal.

This is not just recycling. It is an industrial transformation.

The country has built an energy and materials system where waste has value and where the line between disposal and production has disappeared.

I just watched a Netflix documentary about how bad the garbage disposal situation is, hopefully North America learns how from China 🇨🇳🇨🇦🇺🇸

I live in Denver, Colorado and here there building an enormous mountain with layers of trash. It has grown very large over the years, I assume the layers have environment controls. But all the same, It's still an eyesore for a landfill.